Announcement of the Execution

Source: Jean Maitron, Ravachol et les Anarchistes. Paris, Julliard, 1964;

Translated: for marxists.org by Mitch Abidor;

CopyLeft: Creative Commons (Attribute & ShareAlike) marxists.org 2006.

On the morning of July 11, 1892 Ravachol was executed. The following telegram was sent announcing his death.

Justice was done this morning at 4:05 without incident or demonstration of any kind. He was awakened at 3:40. The condemned man refused the intervention of a chaplain and declared that he had no revelations to make. At first pale and trembling he soon demonstrated an affected cynicism and exasperation at the foot of the scaffold at the moment preceding the execution. In a hoarse voice he sang a few blasphemous and revoltingly obscene lyrics. He didn’t pronounce the word anarchy, and as his head was put in place he gave out a last cry of “Long Live the Re...” Complete calm reigned in the city. Report to follow.

The authorities assumed that the word cut short by the blade was “Republic,” but it is clear that the word was actually "REVOLUTION."

For Feneon and a great many others, aside from hatred of the Third Republic’s imperialist brutalities in Asia and Africa, was anger at the so-called lois scélérates enacted after the attentats of Ravachol, Vaillant, and Henry. These laws banned all revolutionary propaganda, and made those assisting, or even in sympathy with, ‘revolutionaries’ liable to severe punishment. (Camille Pissarro, who had a large police dossier, fled early to the safety of Belgium.).21

Ravachol

By Mitch Abidor

Born François Koeningstein in 1859, Ravachol was perhaps the purest avatar of the ‘bomb-throwing anarchist.’ In a period that didn’t lack for other violent anarchists, like Auguste Vaillant and Emile Henry, Ravachol managed to capture the imagination of those opposed to the corrupt order of the French Third Republic. The novelist Paul Adam was able to say of him: “In this time of cynicism and irony, a saint is born to us.”

A society with horrible divisions of high and low, marked by regular political scandals and large-scale dislocation, France was fertile ground for oppositional movements of all kinds. The short-lived mix of left and right that was Boulangisme, Drumont’s ferocious anti-Semitism (which actually managed to blame floods on the Jews), a growing socialist movement, and various schools of anarchism, all battled for public support.

Ravachol came to stand for the propagandists of the deed; anarchists not interested in organizing mass movements to overthrew the bourgeois order, but who felt that killing the representatives of that order, the worst enemies of the proletariat, would bring about a better world.

Ravachol did not himself have to imagine the horrors of the life of the working-class. Born into a poor family he started working at age eight. A difficult early life, spent wandering France looking for work while being paid a pittance, taught him to hate capitalism. Reading Eugene Sue’s Le Juif Errant at age 18, and attendance at a collectivist circle, made of him a convinced atheist and socialist. Continued reading led him to choose anarchism as his chosen path against the capitalist system.

After years of difficulty, he felt forced to a life of crime as a way of surviving. Few, indeed, are the revolutionary heroes who have grave-robbing as a past occupation, but Ravachol, was neither an ordinary criminal nor anarchist. By this time he had already worked as a counterfeiter and contrebandier. Besides grave robbing, in 1891 he robbed and killed a hermit, and was suspected of other murders as well, for which he was arrested.

Escaping from police custody, in 1892 he embarked on the series of political attacks for which he was to become famous. Avenging the condemnations of a pair of anarchists, he attacked the home of a judge and a government attorney, killing no one while causing considerable property damage.

Captured and put on trial, he was sentenced to hard labor for his political acts, but at a subsequent trial sentenced to death for the murders he had committed. It was at the criminal trial that he attempted to deliver an impassioned and unrepentant speech explaining the causes of his acts and of his revolt, but was cut off before he could do so. When his sentence was announced, his only response was: “Vive l'anarchie!”

He lived on in popular memory. A song was written in his honor, called La Ravachole, and it is said that the word ravacholiser was invented to describe the act of bomb throwing.

Ravachol

by Octave Mirbeau

Translated and introduced by Robert Helms

Francois-Claudius Koeningstein (Oct. 14, 1859 -- July 11, 1892), known to posterity as Ravachol, was born to Dutch and French parents at Saint-Chamond, near St. Etienne in Eastern France. He was angered by two actions taken by the French government on May 1, 1891. One was at Fourmies, where the newly designed Lebels machine gun was used against a peaceful May Day rally at which women and children were carrying flowers and palms. Casualties there numbered 14 dead and 40 wounded. The other incident was at Clichy, where police attacked a six-man anarchist labor rally. The workers defended themselves with pistol-shots and were subsequently given long terms at hard labor.

Ravachol took retribution for the Clichy defendants by bombing the homes of the presiding judge (Mar. 11, 1892) and the prosecutor (Mar. 27, 1892). During the same month he bombed the Lobau Barracks in Paris in response to the Army's slaughter of innocents at Fourmies. These three attentats caused extensive property damage, but no deaths. Ravachol was pointed out to police by a waiter in a restaurant, and then on the night before his trial began on April 25, the restaurant was bombed, killing its owner. A long cycle of vendetta between the anarchists and the government was to follow.

Ravachol's first trial resulted in a sentence of life at forced labor. Octave Mirbeau's article appeared the following week in L'Endehors, 52 (May 1,1892), giving one of the most balanced anarchist views of Ravachol's terrorist activity. Two months later, though, he was extradited to Montbrison in his native region and condemned to death for the killings of an old hermit and a certain landlady he once knew. Before his death Ravachol denied having committed these murders, but he admitted to some burglaries and grave-robbings. He was beheaded at Montbrison and buried there. Today, Ravachol is an important cult hero among French anarchists.

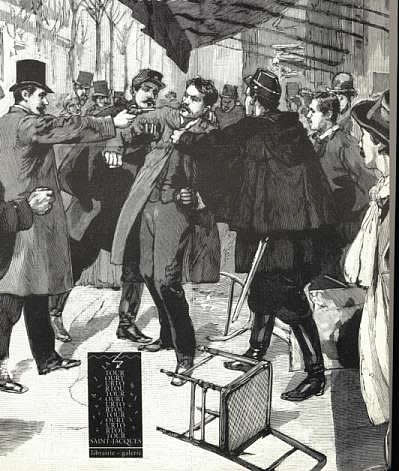

His head escapes the guillotine!

The jurors who have dared to do this, who covered their ears to the barking clamors of death, --were they afraid? Were they afraid to kill a man whose mysterious vengeance won't entirely die with him? Or indeed, beyond the act itself, the awesome horror of which was being howled at them, did they hear the voice of that forward-looking idea, the dominant idea that specifically characterizes this act and ennobles it? I don't know. One never knows what can happen in the conscience of a juror, or what ultimate compulsion he obeys, when dishing out life and death.

The jurors didn't tremble as much as the press that sneered at them, abused them, and damned them. The press wanted blood. Just like the crude middle class, whose blind instincts they reflect, and whose threatened privileges they defend, the journalists are afraid. And fear is a savage thing. For to give itself the illusion of a fierce courage, fear likes to apply rouge to its pale features. They believe, also, that the sound of the legal blade, and the sound of mutilated flesh bouncing on that infamous plank, can drown out the sound of the grinding teeth, the racing pulses, and the voices which grow bolder and angrier every day, boiling up from the hellish underbelly of society. The press is mistaken. There are certain corpses that walk again, and certain voices that won't be stifled. And the void is filled with terrible enigmas.

I am horrified by the bloodshed, the ruins, and the death; I love life, and all life is sacred to me. This is why I'm going to ask for the anarchist ideal which no form of government can create: love, beauty, and peace between men. Ravachol doesn't frighten me. He is as transient as the terror he inspires. He is the thunder clap that is followed by the glory of the sun and the calm sky.

Beyond the somber task at hand smiles the admirable Kropotkin's dream of universal harmony.

Besides, our society has no right to complain, since it has given birth to Ravachol: it sowed misery, and reaped revolution.

This is just.

And this begs the question...

Who is it --throughout this endless procession of tortures which has been the history of the human race --who is it that sheds the blood, always the same, relentlessly, without any pause for the sake of mercy? Governments, religions, industries, forced labor camps, all of these are drenched in blood. The murder is weary of their laws, their prayers, and their progress. Again just recently, there were the frenzied butchers who turned Paris into a slaughterhouse as the Commune perished. There were pointless massacres, such as at Fourmies where the bodies of innocent women and little kids tried out the ballistic virtues of the Lebels machine gun for the first time. And there are always the mines in which fifty, a hundred, or five hundred poor devils are suffocated, swallowed in a single moment of horrible destruction, their charred bodies never to see daylight again. And there are also the horrid conquests of distant countries where happy races, unknown and peaceful, groan under the boot of that robber of continents, that filthy rapist of forest communities and virgin lands, the western slave trader.

Each footstep taken in this society bristles with privileges, and is marked with a bloodstain; each turn of the government machinery grinds the tumbling, gasping flesh of the poor; and tears are running from everywhere in the impenetrable night of suffering. Facing these endless murders and continuous tortures, what's the meaning of society, this crumbling wall, this collapsing staircase?

We live in ugly times. The misery has never been worse, because it's never been more obvious, and it's never stood closer to the spectacle of wasted riches and the promised land of well-being from which it is relentlessly turned away. Never has the law, which protects only the banks, pressed so hard upon the tortured shoulders of the poor. Capitalism is insatiable, and the wage system compounds the evils of ancient slavery. The shops are packed full of clothing, and there are those who go about completely naked; the indifferent rich are puking up food, while others perish from hunger in their doorways. No cry is heeded: whenever a single, louder complaint penetrates the din of sad murmurs, the Lebels is loaded and the troops are mobilized.

And that's not all.

A population does not live solely on its stomach. It also has a life of the mind. Its intellectual joys are just as necessary as its physical joys. It has a right to beauty just as it has a right to bread. Indeed, those who could give it its higher pleasures, those who could introduce to the people this vital beauty are treated like public enemies, hunted down as criminals, hounded for being anarchists and beaten like beggars. They are reduced to a solitary life. An enormous barrier separates them from the crowd, by whom they are regarded as repulsive spectacles, and over whom there is spread the enormous, sordid, impenetrable veil of triumphant stupidity. We are witnessing an incredible social moment: at this time, while abundant with great thinkers, the public taste has never been so degraded, nor has ignorance ever enjoyed such base pleasures. Surely, if the hour in which we live is hideous, it is formidable as well: it's the hour of popular awakening. And this hour is full of uncertainty. The patience of the downtrodden and the dispossessed has lasted long enough. They want to live, they want to enjoy, they want their share of all the happiness and sunshine. Whatever the rulers do, reacting to their worst fears, they will not forestall the inevitable course of events. We're touching upon a decisive moment in human history. The old world is collapsing under the weight of its own crimes, and is itself lighting the fuse of the bomb that will blast it all away. This bomb will be all the more terrible because it will contain neither gunpowder nor dynamite. It'll contain compassion and an idea; two forces against which nothing can be done.

Feneon's shadowy political life during the culminating years of the anarchists' influence on French culture in the decade stretching from the mid-1880's to the assassination of President Sadi Carnot in 1894. Feneon's association with the anarchist cause was no secret at the time. He wrote for anarchist journals like the Revue Anarchiste, and the hard-line, slangy and irreverent Le Pere Peinard (The Old Work Horse), usually as an anonymous contributor since the police were gathering a sizable dossier on Feneon's political associations and activities.

What strikes one as surprising is the extent of anarchist sympathy in turn-of-the-century Paris; it cut across most aspects of society from the intellectual elite to the working poor. The two most prominent anarchist journals of the period sold 10,000 copies a week between them.

Unlike most of the readers of such journals, Feneon, as a contributor, was a professed believer in ''Propaganda of the Deed,'' rather than ''Propaganda of the Word.'' Feneon, however, had become increasingly militant in his politics and was a professed believer in the second alternative. An anarchist friend of his, Emile Henry, had launched two bomb attacks, one of which killed an office boy and four policemen, and the other, in a crowded cafe, seriously wounded 20 people, one of whom subsequently died. Caught by pursuing waiters at whom he fired his revolver, Henry was tried and was guillotined in 1894. (Feneon wrote about the ''intimate charm'' of the first bombing, referring perhaps to the fact that the bomb had been made with a kitchen pot.) Ms. Halperin's report of one of Feneon's conversations with Signac reveals that Feneon considered the bombing of the Cafe Terminus the most justified of the recent Parisian bombings. It had been ''directed toward the voting public, more guilty in the long run, perhaps, than the representatives they elected to office.''

Not long after Henry's capture, Feneon himself was arrested and charged with the bombing, on April 4, 1894, of the crowded, fashionable ground-floor restaurant of the Hotel Foyot. (Ironically, given Feneon's lovely gesture in the Signac painting, the bomb was concealed in a flowerpot.) There was considerable property damage but only one of the diners was seriously wounded.

Held at Mazas Prison for several months - he busied himself translating Jane Austen's ''Northanger Abbey'' - Feneon was put on trial in August, with a number of anarchists and sympathizers the Government had rounded up, in what became known as the Trial of the 30. The Government's case was badly handled and based largely on circumstantial evidence. Supported by the testimony of friends in the newspapers and at the trial by Mallarme and Feneon's boss at the War Office, as well as by a clever defense by his attorney, Feneon - along with most of the defendants - was acquitted.

POURQUOI ET COMMENT

Le Père Peinard s'est bombardé Journaleux

Almanach du Père Peinard, 1894

Ce que le temps passe, mille marmites ! Y'a de ça cinq années, quasiment.

La Boulange faisait alors tourner la boule au populo ; à l'élection du 27 janvier 89, la foultitude d'affiches qui salissaient les murs de Paris me donna envie d'y aller de la mienne.

Entre deux savates, j'accouchai de la Première du Père Peinard au Populo.

Sans me pousser du col, le flanche fut bougrement gobé. A telle enseigne que ça me mit l'eau à la bouche : l'idée me vint de continuer le fourbi, et de tailler de régulières bavettes avec le populo.

Faire un journal ?... Mince de tintouin ! Je ne refoulai pas, mille dieux. J'avais quelques pélos en poche : je risquai le paquet.

Le bon fieu qui, le plus souvent, torche les dessins de la huitième page, colla ma trombine sur le papier. Bons bougres, levez le nez de trois pouces, la gueule en question est juste au-dessus de la tartine.

Ça fit une couverte à mes réflecs. Ah mais, foutre, le numéro n'était pas grandelet ! A peine s'il était large comme la main.

Depuis le caneton s'est emplumé, il a ouvert ses aîles, bec et ongles lui ont poussé.

Turellement, sur les foultitudes de camaros inconnus avec qui je jacasse aujourd'hui toutes les semaines, y en a bougrement qui n'ont jamais reluqué le commencement de mes flanches.

Pour ceux-là, afin de faire plus ample connaissance, je vas leur servir quelques tranches des tartines de mon premier numéro, qui parut le 24 février 1889.

Voici :

Si rigolboche que ça paraisse, ça y est, me voilà journaliste.

Comment c'est venu, en quatre mots le voici : depuis un brin de temps, un tas d'idées me trottaient par la caboche, et ça me turlupinait rudement de n'en pas pouvoir accoucher. Voir cette fin de siècle, dégueulasse au possible, où tout est menteries, crapuleries et brigandages, — et assister la bouche close à tout ça : nom de dieu, je pouvais pas m'y faire ! Almanach du Père Peinard, 1894 Ce que le temps passe, mille marmites ! Y'a de ça cinq années, quasiment. La Boulange faisait alors tourner la boule au populo ; à l'élection du 27 janvier 89, la foultitude d'affiches qui salissaient les murs de Paris me donna envie d'y aller de la mienne. Entre deux savates, j'accouchai de la Première du Père Peinard au Populo. Sans me pousser du col, le flanche fut bougrement gobé. A telle enseigne que ça me mit l'eau à la bouche : l'idée me vint de continuer le fourbi, et de tailler de régulières bavettes avec le populo. Faire un journal ?... Mince de tintouin ! Je ne refoulai pas, mille dieux. J'avais quelques pélos en poche : je risquai le paquet. Le bon fieu qui, le plus souvent, torche les dessins de la huitième page, colla ma trombine sur le papier. Bons bougres, levez le nez de trois pouces, la gueule en question est juste au-dessus de la tartine. Ça fit une couverte à mes réflecs. Ah mais, foutre, le numéro n'était pas grandelet ! A peine s'il était large comme la main. Depuis le caneton s'est emplumé, il a ouvert ses aîles, bec et ongles lui ont poussé. Turellement, sur les foultitudes de camaros inconnus avec qui je jacasse aujourd'hui toutes les semaines, y en a bougrement qui n'ont jamais reluqué le commencement de mes flanches. Pour ceux-là, afin de faire plus ample connaissance, je vas leur servir quelques tranches des tartines de mon premier numéro, qui parut le 24 février 1889. Voici : Si rigolboche que ça paraisse, ça y est, me voilà journaliste. Comment c'est venu, en quatre mots le voici : depuis un brin de temps, un tas d'idées me trottaient par la caboche, et ça me turlupinait rudement de n'en pas pouvoir accoucher. Voir cette fin de siècle, dégueulasse au possible, où tout est menteries, crapuleries et brigandages, — et assister la bouche close à tout ça : nom de dieu, je pouvais pas m'y faire ! Le sang me bouillait de voir les cochons du gouvernement s'engraisser à nos dépnes ; de ces bougres-là, y en a pas un seul qui vaille mieux que l'autre. Dans les Chambres, de l'Extrême-Droite à l'Extrême-Gauche, il n'y a qu'un tas de salopiauds tous pareils : Cassagnac, Freppel, Ferry, Floquet, Boulanger, Basly et les autres, c'est tous des bouffe-galette ! La rosserie des patrons aussi me foutait en rage. Ces chameaux-là n'en fichent pas un coup ! Ils rappliquent à l'atelier une fois leur chocolat liché ; ce qu'ils savent faire chouettement, c'est gueuler après les compagnons et palper la bonne argent, — sortis de là, il n'y a plus personne. Y a bien les journalistes de métier qui pourraient parler et en dire long, contre les riches et les puissants ; mais voilà ils trouvent plus profitable de rabâcher les vieilles balançoires. Le nez au cul des bourgeois, des financiers, des gouvernants, ils ne cherchent qu'à empocher des pièces de cent sous. Et dam, comme ils y trouvent leur profit, ils sont muets comme des carpes. — Y a pas, c'est un truc épatant pour empêcher les chiens de mordre, que de les attacher avec des saucisses !... Donc, je répétais souvent : y aura donc pas un gas à poil qui ait le nerf de gueuler toutes ces vérités, nom de dieu ? A force d'y penser, d'en causer avec des copains, je me suis dit : «Pourquoi pas moi ? Si l'instruction est un peu de sortie, y a du bon sens dans ma caboche !...» * Naturellement, en ma qualité de gniaff, je ne suis pas tenu à écrire comme les niguedouilles de l'Académie : vous savez, ces quarante cornichons immortels, qui sont en conserve dans un grand bocal, de l'autre côté de la Seine. Ah, non alors, que j'écrirai pas comme eux ! Primo, parce que j'en suis pas foutu, — et surtout parce que c'est d'un rasant, je vous dis que ça... Et puis, il faut tout dire : la grammaire que j'ai eu à l'école ne m'ayant guère servi qu'à me torcher le cul, je ne saisis pas en quel honneur je me foutrais à la piocher maintenant. Il est permis à un zigue d'attaque, de la trempe de bibi, de faire en jabotant ce que les gourdes de l'Académie appellent des cuirs.Et j'en fais, mille tonnerres, je suis pas bouiffe pour des prunes !

Emile Henry February 27, 1894

Letter to the Director of the Conciergerie

Translated: for marxists.org by Mitchell Abidor.

This text was written from jail just two weeks after Henry had thrown a bomb at Paris’ Café Terminus, killing one and injuring twenty.

During the visit you made to my cell Sunday, the 18th of this month, we had a quite friendly discussion of anarchist ideas.

You said you were very surprised to learn our theories in a different light, and you asked me to summarize our conversation in writing, in order to better know what the anarchists want.

You can easily understand, monsieur, that in just a few pages one can’t expound upon a theory which analyses our current social life in all of its manifestations; that studies these manifestations the way a doctor examines a sick body, and which then condemns them because they’re contrary to human happiness and, in place of them, builds an entirely new life, based on principles completely antagonistic to those upon which the old society was built.

Besides, others have already done what you ask of me: Kropotkin, Reclus, Sébastien Faure have set forth their ideas, and pushed their development as far as possible.

Read Évolution et Révolution by Reclus, La Morale Anarchiste, Les Paroles d’un Révolté, La Conquete du Pain by Peter Kropotkin; Autorité et Liberté, Le Machinisme et ses Conséquences by Sébastien Faure; La Société Mourante et l’Anarchie by Grave; Entre Paysans (Fra Contadini) by Malatesta; read also the numerous pamphlets and manifestoes that have appeared over the last fifteen years, each expounding new ideas, according to whether study or circumstances suggested them to their authors.

Read all of this and then you would form a well-founded judgment on anarchy.

Nevertheless, don’t think that anarchism is a dogma, a doctrine that can’t be attacked, indisputable, venerated by its followers as the Koran is by Muslims.

No, the absolute freedom that we call for ceaselessly expands our ideas, raises them towards new horizons (following the will of diverse individuals) and removes them from the rigid frameworks of regimentation and codification.

We are not “believers;” we don’t bow before Reclus or Kropotkin. We debate their ideas, we accept them when they develop sympathetic impressions in our brains, but we reject them when they don’t strike a chord within us.

We are far from possessing the blind faith of the collectivists, who believe in something because Guesde said it had to be believed in, and who have a catechism whose paragraphs it would be sacrilegious to dispute.

This being established, I am going to try to briefly and rapidly expound for you what I understand by anarchy, without involving other comrades who, on certain points, could have views different from mine.

You would not dispute the fact that the current social system is evil, and the proof that it is, is that everyone suffers from it. From the poor itinerant, with neither bread nor roof, who knows constant hunger, to the millionaire, who lives in fear of a revolt of the poor that would trouble his digestion, all of humanity lives in a state of anxiety.

On what bases does bourgeois society rest? Putting aside the principles of family, fatherland, and religion, which are nothing but corollaries, we can affirm that that the two cornerstones, the two fundamental principles of the current state are authority and property.

I don’t want to go on any longer on this subject: it would be easy for me to prove that all the ills we suffer from flow from property and authority.

Poverty, theft, crime, prostitution, war, revolution are all nothing but the results of these principles.

The two bases of society being thus evil, there is no reason to hesitate. There’s no need to try any of a group of palliatives (e.g. socialism) that serve only to shift the wrong. The two vicious germs must be destroyed, and eradicated from social life.

This is why we anarchists want to replace private property with communism, and authority with freedom.

No more deeds of possession or domination: absolute equality.

When we say absolute equality we don’t claim that all men will have the same brain, the same physical organization: we know that there will always be the greatest diversity in cerebral and physical aptitudes. It is precisely this variety of capacities that will bring into being the production of all that is necessary for humanity, and we count on this as well to maintain emulation in an anarchist society.

There will be engineers and laborers: this is obvious. But one will not be considered superior to the other, since the work of the engineer is useless without the collaboration of the laborer, and vice versa.

Everyone being free to choose his trade, there will exist only beings that obey, without any constraints, the leanings nature places in them (guarantee of good productivity).

Here a question must be asked: And the lazy? Will everyone want to work?

We answer yes, everyone will want to work, and here is why:

Today, the average workday is ten hours.

Many workers are kept busy at labors that are absolutely useless to society, in particular on armaments for the army and navy. Many are also unemployed. Add to this a considerable number of able-bodied men who produce nothing: soldiers, priests, policemen, magistrates, civil servants, etc.

We can thus say, without being accused of exaggeration, that of a hundred capable of producing some kind of labor, only fifty furnish an effort truly useful to society. It is these fifty who produce all of society’s riches.

From this flows the deduction that if everyone worked, instead of ten hours the workday would decrease to only five.

Beyond this we should consider that in the current state of things the total of manufactured products is four times, and of agricultural products three times the amount required to meet humanity’s needs; which is to say that a humanity three times more numerous would be clothed, housed, heated, fed; in a word, would have all of its needs satisfied if waste and other causes didn’t destroy that overproduction. (You will find these statistics in the little pamphlet: “The Products of the Land and of Industry”).

From what has gone before, we can draw the following conclusion:

A society where all would work together, and which would be satisfied with productivity not far beyond its consumer needs (the excess of the first over the second would constitute a small reserve) would have to ask of each of its able-bodied members an effort of only two or three hours, perhaps less.

Who would then refuse to give such a small quantity of labor? Who would want to live with the shame of being held in contempt by all and being considered a parasite?

...Property and authority march together, the one supporting the other to keep humanity enslaved.

What is the right to property? Is it a natural right? Is it legitimate that one eats while the other fasts? No. Nature, in creating us, made us with similar organisms, and the laborer’s stomach demands the same satisfaction as that of the financier.

Nevertheless, one class today has taken all, stealing from the other class the bread not only of its body, but also of its soul.

Yes, in a century that we call one of progress and of science, is it not painful to think of the millions of intelligences hungry for knowledge and that cannot flourish? How many children of the common man, who could have become men and women of great value, useful to humanity, will never know anything but the few indispensable notions taught in elementary school.

Property! That is the enemy of human happiness, for it alone creates inequality, and in its train hatred, envy, bloody revolt...

Established authority serves no other purpose than the sanctioning of property. It is there to put force at the service of the act of despoiling.

Work being a natural need you will accept along with me that no one would flee from the demand of as minimal an effort as that which we spoke of above.

(Labor is so natural a need that History shows us several statesmen treating themselves with joy from the cares of politics to work as simple laborers: To cite two well-known cases: Louis XVI worked with locks, and in our day Gladstone, “The Great Old Man” [ in English in the original] profits from his vacations to himself chop down some of the oaks of his forests, like a common lumberjack).

So you see, monsieur, there would be no reason to have recourse to the law to avoid the problem of idlers.

But if in some extraordinary case someone wanted to refuse his assistance to his brothers, it would still be less costly to feed this unfortunate, who can only be described as sick, than to maintain legislators, magistrates, police and prison wardens to break him down.

Many other questions arise, but they are of a secondary nature, the most important thing being to establish that the suppression of property would not cause a cessation of production due to the development of laziness, and that anarchist society would know how to feed itself and satisfy all of its needs.

All the other objections that can be raised will be easily refuted by taking inspiration from the idea that an anarchist milieu would cause to grow in each of its members the love of and solidarity with his like, for man will know that in working for others he works for himself.

A seemingly better-founded objection is the following:

If there is no more authority, if there is no fear of the gendarme to stop the criminal’s arm, don’t we risk seeing crimes and misdemeanors multiply at a frightening rate?

The answer is easy:

We can categorize the crimes committed today in two principal categories; crimes of interest and crimes of passion.

The first group will disappear on its own, since there can be no attacks on property in a milieu which has done away with property.

As for the second group, no law can stop them. Far from this being the case, the current law – which acquits a husband who kills his adulterous wife – does nothing but favor the frequency of these crimes.

On the contrary, an anarchist milieu would raise the moral level of humanity Man will understand that he has no rights over a woman who gives herself to another man, since that woman does nothing but follow her nature.

Consequently crimes, in a future society, will become increasingly rare, until they disappear completely.

Monsieur, I am going to summarize for you my ideal of an anarchist society.

No more authority, which is far more contrary to human happiness than the few excesses that could occur at the beginning of a free society.

In place of the current authoritarian organization, the grouping of individuals by sympathies and affinities without laws or leaders.

No more private property; the gathering in common of products; each one working and consuming according to his needs, which is to say, as he wishes.

No more family, selfish and bourgeois, making man the property of woman and woman the property of man; no more demanding of two beings who loved each other but a moment that they remain attached till the end of their days.

Nature is capricious: it always demands new sensations. It wants free love. This is why we want free unions.

No more fatherlands, no more hatred between brothers, pitting against each other men who have never set eyes on each other.

Replacement of the narrow and petty attachment of the chauvinist for his country by the large and fruitful love of all of humanity, without distinction of race or color.

No more religions, forged by priests to degrade the masses and give them the hope of a better life, while they themselves enjoy life in the here and now.

On the contrary, the continual expansion of the sciences, put within the grasp of every being who will feel attached to their study, little by little bringing all men to a materialist consciousness.

The particular study of hypnotic phenomena, which science is beginning to become aware of, in order to unmask the charlatans who present to the ignorant, in a marvelous and superstitious light, facts which are purely physical.

In a word, absolutely no more hindrances to the free development of human nature.

The free blossoming of physical, cerebral and mental faculties.

I am not so optimistic as to believe that a society built on such foundations will arrive at perfect harmony. But I have the profound conviction that two or three generations will suffice to tear mankind from the influence of the artificial civilization which it submits to today and to return it to the state of nature, which is the state of goodness and of love.

But in order to make victorious this ideal, to set anarchist society on a solid base, we must begin with the work of destruction. The old, worm-eaten edifice must be torn down.

This is what we are doing.

The bourgeoisie claims that we will never arrive at our goal.

The future, the very near future, will teach them.

Vive l’Anarchie!

Works of Ravachol 1892

My Principles

Source: Un saint nous est né, edited by Philippe Oriol. L'équipement de la pensée, Paris. 1992;

Translated: for marxists.org by Mitchell Abidor;

CopyLeft: Creative Commons (Attribute & ShareAlike) marxists.org 2006.

While in prison, this document was dictated to the police by Ravachol. It remained unpublished until the historian Jean Maitron found it in the Paris Police Archives in 1964.

The above named, after having eaten his fill, spoke to us as follows:

“Messieurs, it is my habit, wherever I am, to do propaganda work. Do you know what anarchism is?”

We answered ‘No’ to this question.

“This doesn’t surprise me,” he responded. “The working class which, like you, is forced to work to earn its bread, doesn’t have the time to devote to the reading of pamphlets they’re given. It’s the same for you.

“Anarchy is the obliteration of property.

“There currently exist many useless things; many occupations are useless as well, for example, accounting. With anarchy there is no more need for money, no further need for bookkeeping and the other forms of employment that derive from this.

“There are currently too many citizens who suffer while others swim in opulence, in abundance. This situation cannot last; we all should profit by the surplus of the rich; but even more obtain, like them, all that is necessary. In current society, it isn’t possible to arrive at this goal. Nothing, not even a tax on income, could change the face of things. Nevertheless, the bulk of workers think that if we acted in this way, things would improve. It is an error to think this way. If we tax the landlord, he’ll increase his rents and in this way will arrange for those who suffer to pay the new charges imposed on them. In any event, no law can touch landlords for, being the masters of their goods, we can’t prevent them from doing whatever they want with them. What, then, should be done? Wipe out property and, by doing this, wipe out those who take all. If this abolition takes place, we have to also do away with money, in order to prevent any idea of accumulation, which would force a return to the current regime.

“It is in effect money that is the cause of all discord, all hatred, of all ambitions; it is, in a word, the creator of property. This metal, in truth, has nothing but an agreed upon price, born of its rarity. If we were no longer obliged to give something in exchange for those things we need to live, gold would lose its value and no one would seek it. Nor could they enrich themselves, because nothing they would amass could serve them in obtaining a better life than that of others. There would then no longer be any need of laws, no need of masters.

“As for religions, they’d be destroyed, because their moral influence would no longer have any reason for existence. There would no longer be the absurdity of believing in a God who doesn’t exist, since after death everything is finished. So we should hold fast to life, but when I say life I mean life, which does not mean slaving all day to make the bosses fat and, while dying oneself of hunger, become the authors of their well-being.

“Masters aren’t necessary, these people whose idleness is maintained by our labor; everyone must make himself useful to society, by which I mean work according to his ability and his aptitude. In this way, one would be a baker, another a teacher, etc. Following this principle, work would diminish, and each of us would have only an hour or two of work a day. Man, not being able to remain without some form of occupation, would find his distraction in work; there would be no lazy idlers, and if they did exist, there’d be so few of them that we could leave them in peace and, without complaint, let them profit from the work of others.

“There being no more laws, marriage would be destroyed. We would unite by inclination, and the family would be founded on the love of a father and mother for their children. For example, if a woman no longer loved he who she had chosen as a companion, she could separate from him and form a new association. In a word, complete freedom to live with those we love. If in the case I just cited there were children, society would raise them, that is to say, those who will love the children will take them in charge.

“With this free union, there will be no more prostitution. Secret illnesses would no longer exist, since these are only born of the abuse of the coming together of the sexes; an abuse to which women are forced to submit, since society’s current conditions oblige them to take this up as a job in order to survive. Isn’t money necessary in order to live, earned at whatever cost?

“With my principles, which I can’t in so little time lay out in full detail, the army will no longer have any reason to exist, since there will no longer be distinct nations; private property would be destroyed, and all nations would have joined into one, which would be the Universe.

“No more war, no more disputes, no more jealousy, no more theft, no more murder, no more court system, no more police, no more administration.

“The anarchists have not yet gone into the details of their constitution: the mileposts alone have been laid out. Today the anarchists are numerous enough to overthrow the current state of things, and if that hasn’t yet happened, it’s because we must complete the education of the followers, give birth in them to the energy and the firm will to assist in the realization of their projects. All that is needed for that is a shove, that someone put themselves at their head, and the revolution will take place.

“He who blows up houses has as a goal the extermination of all those who, by their social standing or their acts, are harmful to anarchy. If it was permitted to openly attack these people without fearing for the police, and so for one’s skin, we wouldn’t set out to destroy their homes though explosive devices, which could kill the suffering classes they have at their service at the same time as them.”

The Little Ravachols Will Grow Up

By Gustave Mathieu

Source: Ravachol, Un saint nous est né, textes établis et rassemblés par Philippe Oriol. L'Equipemment de la pensée, Paris, 1992;

First Published: L'Endehors, No. 61, July 3, 1892;

Translated: for marxists.org by Mitch Abidor;

CopyLeft: Creative Commons (Attribute & ShareAlike) marxists.org 2006.

An article by Gustave Mathieu, a friend and accomplice of the anarchist hero, written shortly before Ravachol’s execution in 1892.

After all the misadventures of the policemen trailing me and the reporters pursuing me, and in memory of the interest they've always shown me, I perhaps owe them an update.

This is an occasion for me to offer my fraternal hand to the friend that I haven’t forgotten.

If I'm writing these lines it’s not to try to defend Ravachol as a martyr: in the cause for which we fight — sincere, convinced, and without pause — there are no martyrs. Rather than wasting away in a capitalist prison camp, sweating, toiling in order to enrich the exploiters, succumbing to privations and poorly-paid work, isn’t is better to act as a revolutionary?

Can it be said that Ravachol wasn’t called upon to know this sad existence? On the contrary, from an early age he had to work to bring a meager mouthful to his brothers and sisters, brought up in poverty by a mother who had remained a widow.

Of a sickly temperament, and seeing that despite working like a slave his family’s poverty only got worse, he reflected...and he said to himself that rather than suffer like a resigned slave it would be better to take their stolen riches from the exploiters.

He often said: No luxury, only what is necessary. Enough of this life of flabbiness and moral degradation. Dignity, courage and, at the risk of our own lives, let us kill all the exploiters of the world.

Alas, the results of individual propaganda are paid for in a terrible way.

Which is what happened to my friend.

Ravachol bore his head high in front of the lackeys of the magistracy, taking responsibility for his acts, declaring that in our sad society the life of the workers is a hell.

How ironic it is to give all your strength when you're young and to see yourself everywhere rejected when you're old!

You have no right to call yourself an anarchist. You're nothing but a murderer, the cloaked ones answered.

And what are you, you who judge?

The fences of bandits who starve the poor, and of the Lavassiès of all the Comptoirs d'escompte; repulsive beings who approve the idleness of rich playboys and the shooting down of workers, like those of Fourmies, beggars who disturb your digestion. This is what you call order. So be it. You are playing your role, you have force behind you, and, taking advantage of this, you condemned Ravachol to death.

Perhaps you think that, like in the Anstay case, we're going to call for an autopsy of our friend in order to prove that he wasn’t responsible for his acts. Not at all! Ravachol had a healthy mind and a proud heart when he took wherever he found it the money he needed to live, money useful for propaganda: the hermit of Chambles made possible the rue de Clichy. Ravachol’s entire existence followed the logic of the rebel.

And you can kill him, but you'll never be able to stifle the voice of the rebels: the little Ravachols will grow up. You can do what you want, but they'll be more skillful and terrible than their predecessor.

Furthermore, the execution will be a challenge thrown at the anarchists, a challenge that will fall into good hands. The bourgeois press can slander as much as it wants, invent incredible lies, like the kidnapping of the bourgeois Deibler. Let it beware that reality not one day go beyond its predictions.

The squealer Véry, who was so carefully guarded, better even than Deibler now is, nevertheless paid for his denunciation.

If Deibler hasn’t yet thought about retiring, I think for his own safety it would be prudent to impose it on him.

Émile Pouget

POURQUOI ET COMMENT

Le Père Peinard s'est bombardé Journaleux

Works of Ravachol 1892

A Narrative

Source: Ravachol. Un saint nous est né, edited by Philippe Oriol. L'équipement de la pensée, Paris. 1992;

Translated: for marxists.org by Mitch Abidor;

CopyLeft: Creative Commons (Attribute & ShareAlike) marxists.org 2006.

We have three autobiographical texts by Ravachol dating from his time in prison just prior to his execution July 11, 1892. The first was the text dictated to the police, “My Principles”; the second is a longer fragment about his youth, political development and criminal life; and the last an account of his most notorious crime, his attempt at grave-robbing. Supposedly written in his own hand, complete with grammatical and spelling mistakes, it appeared in a Parisian paper two days after Ravachol’s death.

“Among the papers left by Ravachol is found the story of the violation of the grave of Mme la baronne de Rochetaillé. Someone who momentarily had it in his possession having sent it to us, we reproduce it in its entirety, respecting the spelling and grammar. The story is written with a cold and tranquil cynicism, which will inspire in readers the same horror we ourselves felt.”

— Le Gaulois July 13, 1892

...being without work I set myself to making false money, a means not very lucratif and but dangerous, so I soon abbandonned it. I learnd that there was a baroness named de Rochetaillé who had bin buried not to long before. I thought she must have some jewls on her, so I resolved to break into the toomb.

One day I got myself a hooded lamp and a jimmy and I set out.

I left home at 9:00 at night. Along the way I went into a bakery with the intenshun of paying the owner with a two frank piece in exchange for a loaf of bred, but he reconized that it was false. I pretended not to no this and continued along my way. Further along I went into a café and asked for a drink to take with me and I managed to give the owner a two frank piece. Further along I went again to a baker, I asked for a small loaf, I gave him a two frank piece and went on my way.

I got to the cematary at 11:00. Before going in I ate my bred and drank some wine, and climb the wall and head for the grave that I attentively inspect.

So using my jimmy I lifted the toombstone and I entered the toomb; seeing the name I was looking for on a marble stone I set myself to unsealing it with the jimmy. So that the stone shouldn’t fall on me I went into an empty compartment beside it. In falling the stone made a great noise and it broke into many pieces.

I quickly went back up to see if anyone was passing by. Not seeing anything suspishus, I went back down. I broke the 3 or 4 circles that closed the coffin. It wasn’t easy to do this.

Afterward I tried to fit my jimmy into a joint in the coffin and was able to do so. I bust open the planks by pressing on them, but there was a layer of led wrapped around the corpse. I banged on it with the point of the jimmy and managed to make an opening big enough to take out the arm to see her left hand. I had to take out several small pakages which I didn’t know what they contained. Once her left arm was out I pulled it too me and looked attentively at the fingers which was covered with mold. I didn’t find what I was looking for. I looked at the throat and didn’t see nothing there neither, and since my lamp didn’t light anymore since it had no more oil, in order to finish my operation I set on fire a wreath of flowers I'd found in a chapel over the fault. It spred a thick smoke while I was burning which caused me to go back up quickly if I didn’t want to asfixiate.

When I opened the coffin I had only one fear and that was that a large escaping of asfixiating gas would take place, but because I was in a hurry do to a certain need I didn’t hesitate because its preferable to die risking yourself than succumming to hunger.

Once I climbed up I put the toombstone back in place and I started back home but on leaving I saw about a hundred meters away two men coming across the fields who seemed to want to cut me off in order to stop me.

I put my hand on my revolver and slowed down a little. They passed in front of me not saying anything. Later on on the rue da la monta I meet a man who at about a hundred meters who asked the way to the Chateau Creux. I didn’t clearly understand him and he came up to me and repeated the question. I told him to follow me, that I passed write by it. He said to me that I was wearing a fake beard on my face which made me smile since I thought I had nothing to fear from this man who was all alone.

This happened on the rue de la monta. Coming up on the station I showed him the way and continued on mine. I went back home.

No comments:

Post a Comment